The context of resistance

Spaces, times, actors

Spaces:

All these maquis are based on more or less mountainous refuge areas (the Cévennes, the Morbihan, the Morvan, the Glières, the Vercors), or even bocage areas (the Surcouf maquis in Normandy). The originality of the Vercors lies in its strategic geographical position in view of the vital German road and rail communication axes. In the event of a landing in Provence, the penetrating roads of the Rhone valley and the Alps road, the Drôme to Die and Isère to Voreppe bypasses constitute a natural barrier. It is on this originality that the “Montagnards Project” is based.

The times:

The pre-existing modes of resistance in 1940, 1941 and 1942 were strengthened by the contribution of refractory members of the Obligatory Labour Service (STO) from February 1943. In the spring and summer of 1944, most of the refractory fighters had to face violent German attacks, carried out with the aim of weakening them (Bir-Hakeim in the Cévennes, Mont-Mouchet, Saint-Marcel and of course the Vercors), the Germans fearing a general mobilisation of the Resistance.

The actors:

From hard core Resistance fighters – civilians or clandestine soldiers – more or less well organised, the maquis will be forced to take appropriate measures to welcome, hide, house, structure, supervise and arm these future fighters (the Allied parachute drops will provide for this in part.). The numbers mobilised ranged from 500 (Les Glières) to over 2,000 (Vercors, Ain, Saint-Marcel, Surcouf, Mont-Mouchet). In this respect, the Vercors camps were original because of their unity (Franc-Tireur movement), the support of the essentially rural population and their national mission in the event of the “Montagnards Project” being launched. Moreover, the Vercors had to endure the Italian and then German occupations with a balance of power against it.

Another originality of the Vercors lay in its two-headed governance, which was decided at the August 1943 meeting in Darbounouze. In June 1944, the command was twofold: the civilian Eugène Chavant and the military François Huet. All the other maquis had only one leader, generally an officer.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The spaces

Set between cliffs, the Vercors is for the purists a massif of the Pre-Alps, and a Plateau for the vox populi, i.e. the resistance fighters and, often, the press or certain works. The Vercors massif is the largest (some 2,000 km2) of the northern pre-Alpine massifs. It is administered by the Isère department, for the Quatre-Montagnes area, and by the Drôme department, for the traditional or historical Vercors area. As a result, the Vercors has long lacked geographical, social and economic unity.

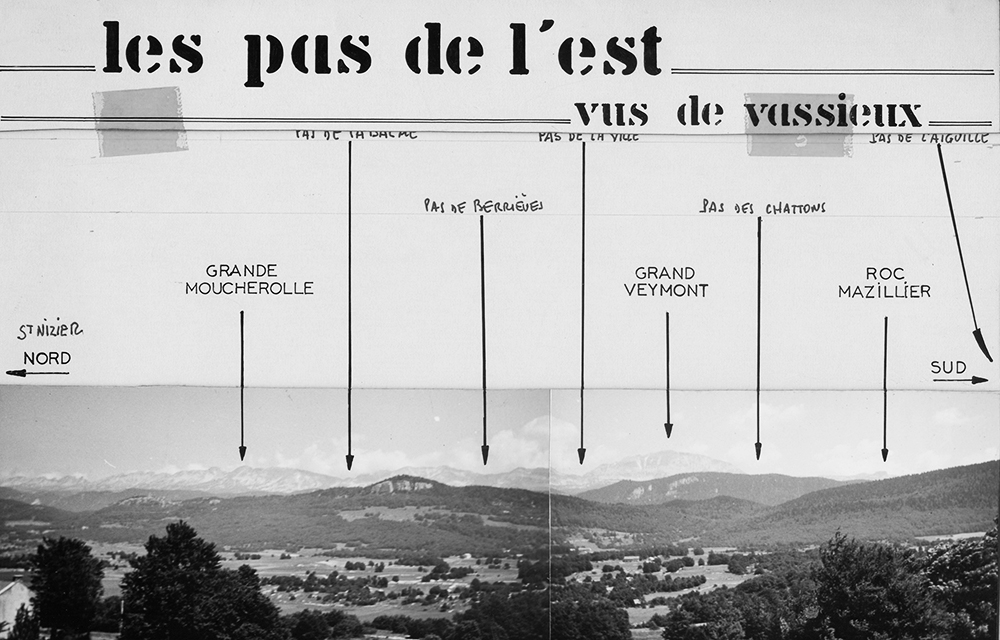

It is generally triangular in shape, with an average width of about 40 kilometres and a length of 60 kilometres. It is a very uneven relief made up of high cliffs, cluses and gorges. But there are also synclines that soften the landscape (Val-de-Lans). The Royans to the west, the Trièves to the east, the Gervanne and the Diois to the south should be added to the well identified massif, notably by Raoul Blanchard and Jules Blache. These areas are important for observing the various exchanges between the massif and its foothills and the organisation of the Resistance. It is on these areas that the sectors of the Resistance were modelled. Communications to the outside world are rare and range from roads cut into defiles to mule tracks and even footpaths.

Its economy is essentially rural and pastoral. The mountain pastures for the summer transhumance give rise to the construction of shepherd’s huts or high altitude chalets, often dilapidated, which are refuges for the resistant, despite the scarcity of springs on these karstic grounds. Finally, the massif has extensive forest cover. It generates a forestry activity and the exploitation of charcoal, but it is also a potential refuge area for the existence of maquis.

The violence of the fighting in the summer of 1944, marked by the massacre of civilians, and the memories associated with these tragedies contribute to the unity of the massif. Finally, the development of tourism and the creation of the Vercors Regional Natural Park have contributed to creating this unity.

Authors: Julien Guillon and Guy Giraud

Source:

From Blache Jules, Les Massifs de la Grande Chartreuse et du Vercors, Grenoble, Didier & Richard, 1931, republished by Laffitte reprints, Marseille, 1978.

The Vercors, a natural refuge zone

Like other mountainous and wooded regions, the Vercors was a natural refuge area for clandestines who gradually evolved into armed maquis. Its valleys and plateaus, protected by cliffs, were ideal for receiving parachute drops. Dominating the German communications linking Toulon and Marseille to the Lyonnais, the Vercors proved to be a possible base of departure to threaten the Germans, in support of an allied landing on the Provençal coast.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The times

Course of events from 1940 to 1945 – What direct or indirect implications for the Vercors?

1940

- On 25 June, the armistice with Germany and Italy came into force. France was partly occupied, and refugees reached the southern zone, particularly the natural refugee zone of the Vercors.

1941

- December, publication of the first issue of Franc-Tireur and Combat.

1942

- 2 January, Jean Moulin (Max) is parachuted into the southern zone.

- 14 July, Free France renames itself “Fighting France”.

- 11 November, the Germans invade the southern zone.

- 12 November, the Italians occupy the Alpine region.

- December, creation of the Metropolitan Army Organisation (OMA, future Organisation de Résistance de l’Armée, ORA).

1943

- 30 January, creation of the militia.

- 16 February, Vichy mobilises three age groups for the Obligatory Labour Service (STO). First camp in the Vercors at Ambel.

- 9 June, arrest of General Delestraint (Vidal), who had ratified the “Montagnards Project” drawn up by P. Dalloz.

- 21 June, arrest of Jean Moulin in Caluire. He had unified the Resistance movements and supported the “Montagnards Project”.

- 8 September, Badoglio signed the armistice with the allies. The Italians left their zone. The Germans occupied Grenoble.

- 13 November, first parachute drop of weapons on the Vercors.

- 20 November, creation in Algiers of the General Directorate of Special Services (DGSS).

1944

- Beginning of the year, occasional actions by the Germans on the Vercors.

- 8 and 9 June, lockdown of access to the Vercors by the maquis.

- 3 July, proclamation of the Republic in Vercors.

- 21 July until the beginning of August, German assault on the Vercors.

- 23 July, distribution of the order to disperse the maquis.

- At the end of the year, fighting continues for the Liberation.

1945

- 8 May, German capitulation.

Author: Guy Giraud

Source:

In 2015, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Rochelle pocket,

the Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Rochelle highlighted the singular events experienced by the city and its inhabitants.

The main times of the Vercors

1940

After the signing of the armistice on 22 June, the Germans were stopped at the Voreppe cluse. They did not enter the Vercors. Refugees, fleeing the occupied zone, sought refuge behind the cliffs of the massif. The Cyprian-Norwid Polish high school settled in Villard-de-Lans. An informal resistance movement emerged on 18 June.

1941-1942

Individuals, or even small teams, tried to organise themselves clandestinely, marking the beginnings of forms of resistance to the invader, as in Villard-de-Lans, Grenoble and Romans.

- On 6 April 1942, contacts between the Villard-de-Lans and Grenoble nuclei were established discreetly.

- November 1942-September 1943: The Italians occupied the Alpine zone east of the Rhône.

- 11 November 1942: the Germans invaded the free zone; the Italians were driven home.

- December 1942: P. Dalloz imagines a strategic role for the Vercors, in support of an allied landing on the coast of Provence. Later, this project will receive the assent of Y. Farge, Jean Moulin and General Delestraint. It was approved by the Free French services. 1943

- January: installation of the first camp in Ambel.

- February 1943: introduction of the Obligatory Labour Service (STO).

- March-April: constitution of the first combat committee.

- May-June-July: arrests of Aimé Pupin, General Delestraint and Jean Moulin.

- End of June: constitution of the second combat committee.

- 10th and 11th August: meeting of the leaders of the Vercors Resistance at Darbounouse.

- 13th November: first parachute drop of arms at Darbounouse.

From January to June 1944, events accelerated:

- The militia and the Germans carried out raids and attacks on the Vercors.

- The Vercors received parachute drops of weapons.

- The governance of the Vercors evolves: E. Chavant had been in charge of it since December 1943 and was in Algiers from 24 May to 7 June. On 4 January, N. Geyer became the military leader; Le Ray handed over powers to him on 31 January. At the end of May, Descour appointed F. Huet to replace N. Geyer.

1944, after 9 June

- On 9 June, the Vercors was mobilised; its accesses were locked.

- At the end of June/beginning of July, the secret services in Algiers and London parachuted in light commandos.

- On 13 and 15 June, the Germans occupied Saint-Nizier-du-Moucherotte.

- 3 July, proclamation of the Republic in Vercors.

- On 12, 13 and 14 July, the Germans bombed La Chapelle-en-Vercors and Vassieux-en-Vercors in reaction to large daytime parachute drops.

- From 21 July, the Germans attacked the Vercors and combed the massif.

- On 23 July, F. Huet gave the order to disperse the maquis units.

- At the beginning of August, the enemy left the plateau; the Resistance reorganised itself to harass the Germans.

- Later on, the fight to liberate the territory continued. A large percentage of fighters will continue the struggle within the 1st army of De Lattre-de-Tassigny, or the 27th alpine division.

Author: Guy Giraud

Source:

From Gilles Vergnon, Le Vercors, histoire et mémoire d’un maquis, Paris, Edition de l’Atelier, 2002, 256 pages.

The actors

The Italians, led by General De Castiglioni, occupied south-eastern France from November 1942 to September 1943. They were not very virulent, but their secret political police service, the Organizzazione di Vigilanza e Repressione dell’Antifascismo (OVRA), was effective. Faced with the development of the Resistance in the Vercors, the enemy progressively engaged its means of action. The Italian occupiers succeeded in eliminating the first Vercors combat committee.

The Germans, led by General Niehoff, invaded the free zone on 11 November 1942 following the Allied landing in North Africa, with the aim of seizing the French fleet at Toulon. They reproached the Italians for their lack of efficiency in the fight against terrorism and the control of Jews. General Pflaum’s 157th DR deployed east of the Rhône, supported by the Sipo/SD (Sichereitsdienst) and the French militia.

The relief of the Italian units gave rise to violent clashes between the two armies, particularly in Grenoble.

At the same time, the resistance was born of individual initiatives or small groups. The decision by the Germans, supported by the Vichy government, to introduce the Compulsory Labour Service (STO) gradually increased the number of people in the refugee zones, which were organised into camps and later into military-type units.

The development of the camps required the establishment of a two-headed civil and military governance. Although this governance underwent changes to compensate for the arrest of some of its members, it was in line with the dual continuity of the Franc-Tireur movement, which brought together civilians and soldiers, and the Montagnards project. Civilians and soldiers sometimes clashed without serious consequences.

The governance led by E. Chavant and F. Huet, from the summer of 1944, was able to master the organisational problems in the areas of support for the population and the organisation of camp structures, particularly at the time of the mobilisation of 9 June 1944.

The Germans, anxious to preserve their freedom of movement on the routes of the Alps and the Rhone valley, engaged in force on 21 July 1944 on the whole of the massif. The outcome of the fighting was a result of the evaluation of the belligerents’ balance of forces.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

Support and equipment for the maquis

Locally, the maquis received the support of the population of the Vercors for its supply, its general security, the supply of false papers and food cards and first aid medical care.

On 14 July 1944, parachuting in the vicinity of Vassieux.

Sometimes, with internal complicity, equipment was stolen from the shops of the Chantiers de la Jeunesse stationed on or near the massif.

The arming of the Resistance remained the major problem; indeed, the recovery of weapons hidden in private homes or taken from the enemy was insufficient both in quantity and in firepower.

However, in order to arm all the volunteers, especially from June 1944 onwards, it was essential to resort to parachute drops that were insisted upon in London and Algiers.

Men trained by the secret services arrived in Vercors. Their leader was R. Bennes (Bob); the team included telegraph operators, coders and decoders of messages sent or received.

Without good radio equipment nothing can be achieved. To set up a link, it is necessary to have the appropriate frequency quartz for sending and receiving messages. Moreover, the addressees in London and Algiers were individualised; they belonged to the Bureau Central de Renseignement et d’Action (BCRA).

The work of a telegraph operator was dangerous because of the technical capacity of the Germans to locate the place of transmission by radio direction finding.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The Camouflage of the material (CDM)

On 22nd June 1940, the armistice was signed with Germany, and on 25th with Italy. The armistice agreement, drawn up at the beginning of July, stipulates:

“The arms, munitions and war material of all kinds remaining in unoccupied territory, insofar as they have not been left at the disposal of the French government for the arming of authorised units, must be stored or placed in security under German or Italian control”.

One of the first forms of the French Resistance, initiated by officers, under the name of “Conservation du Matériel” and then “Camouflage du Matériel”, consisted of clandestinely diverting war material with the ambition of preparing “revenge” following the June defeat. To this end, it circumvented, as far as possible, the occupying forces’ control operations and their armistice commissions. General Louis Colson, the Vichy Secretary of State for War, played a double game between the occupier and this original form of Resistance. Major Émile Mollard, from the army’s general staff, was the linchpin at national level and had representatives throughout the country. In Grenoble, Squadron Leader Henri Delaye, who commanded the regional artillery park, undertook a veritable enterprise of concealing weapons and ammunition in the area around the city. The Vercors was only slightly affected, even though six tonnes of dynamite were stored in a quarry on the Croix-Perrin pass.

Following the Italian and especially German threats, many caches were revealed for fear of reprisals or out of collaboration with the enemy. The recovery of hidden weapons will further expose the Resistance fighters. In trying to recover two CDM trucks hidden in Mens, Captain André Virel launched a poorly conceived operation that led to the decapitation by the Italians of the first combat committee of the massif (notably Aimé Pupin and Remi Bayle de Jessé) in 1943.

Author(s): Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The Armistice Army and the Camouflage of Material (CDM)

The ingenuity of the Resistance fighters of the Armistice Army made it possible to extract military equipment from the control of the occupying forces, whether it was weapons of various types (vehicles, cannons, ammunition, light weapons), or camouflage sites (public buildings, private individuals, transport companies, caves and disused quarries…).

Many of those in charge of the Camouflage du Matériel (CDM) have deputies at both national and local levels.

Despite the possibilities of hiding places offered by its geography, the Vercors was not directly concerned by this type of clandestine operation, with the exception of explosives hidden at the Croix-Perrin pass.

Authors: Guy Giraud, Philippe Huet and Julien Guillon

Arming the maquis

The resistance in the Vercors was gradually organised in the free zone as soon as the armistice was signed on 20 June 1940 with Germany and on 24 June with Italy.

Sten machine gun.

While personalities from Grenoble and Villard-de-Lans, Resistance fighters and clandestines of the first hour, were wondering about the “What to do? “Dalloz came up with a strategic mission for the massif, the Montagnards Project and its annex by Alain Le Ray, specifying the military methods for carrying out the project in conjunction with an Allied landing in Provence. This note envisaged the intervention of 7,500 allied parachutists welcomed and guided by 450 “local” Resistance fighters. Alain Le Ray estimated that 795 machine guns, 795 submachine guns, 6,350 pistols and/or muskets, 5 anti-tank guns and 15 mortars were needed to arm them.

At the same time, a secret military organisation, the Camouflage du Matériel (CDM), tried to evade the inspections of the armistice commissions, particularly in the vicinity of Grenoble thanks to Henry Delaye, squadron leader, who commanded the regional artillery park. In 1943, the Vercors had 2.5 tons of dynamite.

On 10 May 1940, and again on 5 March 1942, the occupying forces banned the possession of weapons throughout the country.

In 1942, the occupying forces introduced the Relève: this law provided for three French technicians to be sent to Germany in exchange for the release of a French prisoner. Faced with the failure of the “Relève”, Germany imposed, on 16 February 1943, the Obligatory Labour Service (STO) for the classes of 1940, 1941 and 1942.

The young STO refractors were forced to seek refuge in the mountainous areas, including the Vercors. Camps were organised and the draft dodgers, who were not yet combatants, were supported, equipped and fed by the population. The nascent governance of the massif appointed camp leaders, organised the number of camp members by thirty or so, and issued orders for the gradual militarisation of the civil organisation, which gradually became civil-military. The first weapons were simple ‘sticks’. Sometimes an inhabitant of the massif, a veteran of the 1914/1918 war, spontaneously brought his weapon and the “old guns” came out of the attics, which constituted, in the beginning, a very basic armament, far from the plans of A. Le Ray. From then on, the question arose as to how to equip these young people with weapons to liberate the massif, against the backdrop of Dalloz’s Montagnards Project.

The disparate weapons recovered were notoriously inadequate in quality and firepower. The call for help from the allies was urgent. The organisation of parachute drops required the use of complicated techniques. The arrival of Robert Bennes and his team of radio operators, connected to London and Algiers, partly solved the problem of equipping the fighters with small arms. However, the units lacked heavy weapons, despite repeated requests from the Vercors government, particularly during the fighting at Vassieux-en-Vercors. On 14 July 1944, a few weeks after the mobilisation order in the field, around 1,200 containers filled with light weapons and various equipment were parachuted in. The violence of the fighting against a regular army was enough to overcome the lack of heavy weapons, despite the “25” guns recovered from the Chambarands military camp in June 1944.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The dilemma of the maquis’ weapons

As soon as the Resistance felt the need to go beyond its genesis in order to reinforce and diversify its clandestine networks, it envisaged armed actions against the occupier, some of them immediately, others in anticipation of the Allied landings on French soil.

The Obligatory Labour Service (STO) brought an influx of draft dodgers into the refugee areas of the Vercors. As a result, camps had to be organised and structured to accommodate and support them.

To go beyond this basic organisation and envisage combat, the dilemma of arming the maquisards arose from the outset. The recovery armament proved to be insufficient. The call for parachute drops in the direction of London and Algiers bore fruit, particularly in the spring of 1944. However, only light weapons were supplied.

At the same time, the Germans structured themselves and reinforced their means of action to counter the rise of the Vercors. During the major battles that took place on the massif, especially at Vassieux-en-Vercors, from 21 to 23 July 1944, the units were ordered to break contact and disperse in order to resume fighting after the Germans had left, as no heavy weapons had been delivered by the Allies or the BCRA.

Author : Guy Giraud

The secret services

The development of the governance of the Vercors, overcoming the vicissitudes of arrests, was based on three constants: the physical unity of the massif, the omnipresence of the Franc-Tireur movement and the Montagnards Project.

The arming and equipping of the maquisards is a recurring problem. Recovered weapons were an insufficient stopgap for military action. Appeals were made to the Allies and to France combattante (Algiers and London) to obtain parachute drops of arms and equipment.

Secret agents were parachuted in to organise these delicate air operations. They had to find parachuting sites that met precise technical standards, define their coordinates on the maps of the time, give them code names, name each drop with a conventional message, which would be broadcast by the BBC, and ensure their collection and camouflage.

For the Vercors, the head of the Section des Atterrissages et des Parachutages (SAP), the name that succeeded the Service des Opérations Aériennes et Maritimes (SOAM), then the Centre d’Opérations de Parachutage et d’Atterrissage (COPA), was Robert Bennes (Bob). Based at La Britière (commune of Saint-Agnan-en-Vercors), he had teams of radio operators parachuted in with the radio sets. Robert Bennes belonged to the SOE (Special Operations Executive).

Other missions were parachuted into the Vercors, with the aim of instructing the maquisards in the use of weapons: this was the case of the Union, Chloroform, Jedburgh and Eucalyptus missions and the Operational Group (OG) Justine.

The Paquebot mission, commanded by Captain Jean Tournissa (Paquebot), was more specifically in charge of the development of a landing field at Vassieux-en-Vercors.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

Essential support from the Allies and the BCRA

After a long phase of development and organisation of the Vercors camps and the decision of 9 June 1944 to mobilise the fighters, the Resistance needed the support of the Allied secret services and the BCRA. This support consisted of parachuting in agents or groups of agents.

These secret agents were mainly responsible for setting up specialised radio links to Algiers and London in order to obtain parachute drops of weapons, equipment, medical supplies, food and tobacco, and sometimes even money. These parachute drops took place on sites identified by their geographical coordinates and whose names were coded. In addition, these secret agents instructed the fighters in the use of weapons.

Robert Bennes (Bob), head of the Section des Atterrissages et des Parachutages (SAP), was the centrepiece of the system on the massif.

Author: Guy Giraud

Operations and missions in the Vercors

Other missions were parachuted into the Vercors; they were responsible for training the maquisards in the handling of weapons, in particular the Union and Eucalyptus missions, the Chloroform mission of the Jedburghs, and finally the Operational Group (OG) Justine.

The Paquebot mission, commanded by Captain Jean Tournissa (Paquebot), was more specifically in charge of the development of a landing ground at Vassieux-en-Vercors.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The parachute drops

The doctrine of the allied general staff was clear: the maquis did not need heavy weapons. In fact, it did not want to over-arm the French Resistance in order to avoid the Communists taking over the governance of France after the Liberation. Moreover, Winston Churchill recommended, in the first instance, concentrating efforts on arming the maquis in Yugoslavia and Greece in anticipation of a possible landing in this region, the idea being to reach Vienna as quickly as possible, and thus cut off the Soviet army’s path. He was not followed by Eisenhower, who imposed the option of landing in Provence after Normandy. The maquis will benefit from a considerable reinforcement in armament in the first half of 1944 (operation “Cadillac”).

The parachute drops were designed according to the rules and standards set by the Allied command, particularly the British. No exception was made for the Vercors. The operations began with the identification of the terrain, which had to be preferably rectangular, in a discreet location, if possible near a wood that could hide the reception committee. The ground must then be homologated, which consists in having it listed by the allied services, in assigning a code and a conventional phrase used to announce the parachute drop.

In the early days, the whole certification procedure was centralised by the British services. After the increase in operations, decisions were more deconcentrated. This is particularly the case for defining conventional phrases. The airfields had particular characteristics according to their ground reception qualities or their environment: Homo for the reception of men, Arma for the reception of equipment, Homo and Arma for mixed areas, such as Vassieux. Only these are permanently activated. The contents of the containers are standardised according to their destination: explosives and accessories, weapons, mines, health equipment, food, clothing, money (sometimes); many are damaged when landing on hard ground.

Authors: Guy Giraud

Amalgam and reconstruction

The Vercors rose up,

It fought,

It suffered,

It continued the fight,

It rose again.

After the departure of the Germans, the maquisards of the Vercors had decisions to make:

- either return to their homes ;

- or to commit themselves individually to fighting or territorial units for the duration of the war, plus three months, to continue the fight in a new environment totally different from that experienced in the maquis in constituted units: 11th Cuir, 6th BCA, First French Army.

The fact of having succeeded in amalgamating these maquisards, deprived of almost everything and untrained in the requirements of modern combat, with a mechanised army from North Africa, equipped and supported by the Americans or the British, will constitute General de Lattre de Tassigny’s greatest victory. The 11th cuirassiers regiment fought all the way to Germany, the 6th BCA joined the new 27th alpine division on the passes of the Alps.

While the fighting for the Liberation of France continued successfully as far as Germany, some of the volunteer veterans who had stayed behind began the difficult task of rebuilding the Vercors and reviving its devastated economy. This was the mission of the National Association of Pioneers and Volunteer Combatants of the Vercors (ANPCVV) under the leadership of Eugène Chavant. The “Swiss donations” would provide significant help from the winter of 1944-1945.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The continuation of the fighting

At the end of the fighting in the Vercors, around 1,500 to 2,000 Resistance fighters signed up for the duration of the war to serve, individually, in fighting units of the 2nd armoured division, De Lattre de Tassigny’s 1st army – Rhine and Danube – in units from the maquis, or in territorial units.

De Lattre de Tassigny wrote: “The common soul of the Rhine and Danube army was born of the intimate and fraternal amalgam of 250,000 soldiers from the Empire and 137,000 FFIs. “

By assimilating the units of the maquis to those of the African Army that landed in Provence, the general wanted to give the Republic an army that was equal to the international recognition of its commitment against the Nazi regime. He also needed to find manpower to make up for his losses and in anticipation of the hard fighting of the winter of 1944-1945 in the Vosges. To succeed in this amalgam, it had to overcome obstacles in the psychological and material fields. Some leaders of the Resistance did not want to be robbed of what they considered their victory against the occupier.

Moreover, the Americans were reluctant to equip the heterogeneous units of the Resistance, whose capacity to adapt to the operational requirements of modern mechanised combat they doubted.

The amalgamation began in the autumn of 1944 and took full effect in February 1945.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

Achieving ‘osmosis’ between the Resistance and a modern army

This amalgam is a double challenge, both from a psychological and a material point of view.

The First Army landed in Provence on 15 August 1944. Its leader, de Lattre de Tassigny, wanted to liberate France and annihilate Nazism. He wanted to give de Gaulle a new army to support his war aims and his policy towards the Allies.

The Resistance fighters were equally motivated to liberate the country. They had heterogeneous units, poorly equipped, with heterogeneous weaponry. They are very attached to their maquis leaders. They do not want to be robbed of what they consider to be their victory. Most of them were unaware of the techniques and tactics of a mechanised army.

De Lattre de Tassigny’s greatest victory was to have succeeded in this delicate operation, despite difficulties coming from the Americans and the British, but also, sometimes, from his own companions.

Authors: Guy Giraud and Julien Guillon

The reconstruction

In August 1944, after the departure of the German troops, the situation was overwhelming: hundreds of maquisards had been killed and several dozen civilians had lost their lives. Hundreds of buildings had been destroyed and the economic circuits had to be reactivated. Agriculture is at half-mast and tourism, which had taken off at the beginning of the 20th century, no longer generates financial income. In the massif, it was therefore imperative to participate in the reconstruction effort; moreover, the mountain climate posed the urgent question of rehousing.

Between 1944 and 1945, numerous private and public initiatives took charge of the cost and practicalities of reconstruction; this was the case in particular with the Comité d’Aide et de Reconstruction du Vercors (C.A.R.V.) and the “Association Nationale des Pionniers et Combattants Volontaires du Vercors”, (A.N.P.C.V.V.) The Ministry of Reconstruction, which relied on its departmental representations (Drôme and Isère) as well as on local initiatives (disaster victims’ associations), also participated in the reconstruction effort, supported by the surge of generosity from Switzerland through the “Swiss Donation” (« Don suisse »).

Gradually, the C.A.R.V. will take over the moral support of the population. Indeed, if all these initiatives will allow the massif to recover little by little, the scar linked to the massacres perpetrated is still difficult to close.

Authors: Julien Guillon

Sources: Archives Départementales de la Drôme

Archives Départementales de la Drôme, 943W13 – 2827W (15-21).

Archives Départementales de l’Isère, 170M5.

Archives ANPCVV- Grenoble.

Gilles Vergnon, Le Vercors: Histoire et mémoire d’un maquis, Paris, éd. de l’Atelier, 2002.

Resiliences

It was a vast territory that had to be rebuilt after the end of the fighting. If the material aspects are essential (houses, farms, public buildings), it is also necessary to heal the wounds of a population particularly bruised by the massacres and atrocities.

Author: Julien Guillon